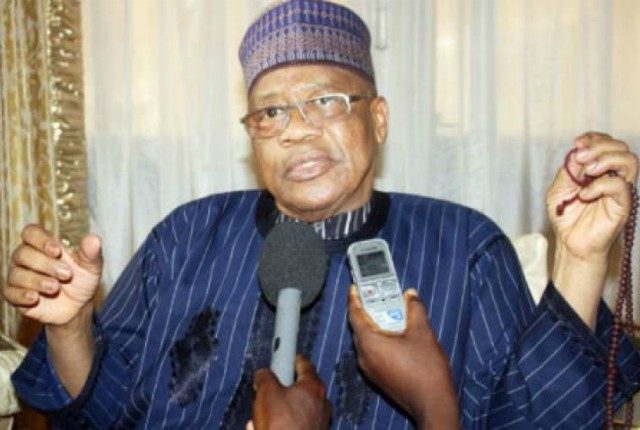

One of Nigeria’s arguably most impactful rulers, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, was 78 years old yesterday. Combatant Officer of the Nigerian Army who joined the force in 1962, IBB, the acronym he became known by while he was Nigerian military Head of State, will go down in history as about Nigeria’s most audacious user of governmental power.

Lethal to those who stood in his way, one of the qualities he possessed at the highest cusp of his rule which even his adversaries acknowledged, was his ambivalent disposition. He had the ability to stand at both ends of the hill and emit fire from his nostrils like a dragon. His off-the-cuff execution of his childhood friend, Mamman Vatsa, in spite of global awe and supplications to him, mirrors this.

But, do majority of Nigerian youth remember Babangida at all? Nigeria is not doing justice to memory by the levity with which it treats history. Remembrancers should flood memories, even of kids in diapers, with stories like the IBB 8-year consequential rule. If you do a census of the youth of today who can retell the tale of IBB’s role in the good and bad that the country reels in today, they must be very far between. This is why those who spiked history out of the curriculum of Nigerian education did Nigeria a lot of harrowing disservice. A chunk of the curriculum, which ought to have been devoted to Nigerian military history, should have had several layers of discussion of IBB’s rule, his mystique and uncommon swagger. They would have learnt how he owns the patent of the pervasive slide into flight of values and monetization of the mind of the Nigerian electorate which are prevalent now, and his incubation of this debasement of values hitherto held aloft by Nigerians.

Babangida participated actively in virtually all the military coups that Nigeria has ever had. In 1966, while a lieutenant colonel with the 1st Reconnaissance Squadron, he was said to have sided with the dissident army corps that forcefully retrieved power from the hands of General Aguiyi Ironsi and sent the huge-statured officer to his untimely grave. In 1975, young Ibrahim was a key participant in the coup that ousted General Yakubu Gowon and, six months later in 1976, after the assassination of Murtala Muhammed, Babangida audaciously walked into the premises of soldier marksmen-strewn Radio Nigeria to test the potency of that persuasive power of his with the ring leader of the coup and one of his best friends, Lt. Colonel Buka Suka Dimka. Babangida had walked into the Radio station to persuade Dimka to abandon his moribund venture of seizing power. He had been sent by General Theophilus Danjuma with the charge to level the premises of the radio station if Dimka failed to bulge. Rather than deploy force however, Babangida chose persuasion.

“The coup has failed,” he reportedly told Dimka. “You have to surrender.” Miffed by IBB’s audacity, Dimka was said to have threatened to shoot him. Flashing that seemingly harmless gap-tooth smile of his, Babangida allegedly told Dimka that he was all right with being killed by his best friend, the sybaritic Dimka. “At least, my wife and children will not suffer under your watch,” he had reportedly told Dimka who in turn melted and asked for amnesty from the new government wherein Babangida would ostensibly play a key role.

With permission to go and discuss the amnesty request from Dimka, IBB reportedly got back to Danjuma who, angered by his audacious request, had thundered, “I didn’t ask you to negotiate!” By the time IBB got back to Radio Nigeria, Dimka was said to have escaped. He was only caught in Abakaliki, current Ebonyi State, while escaping out of Nigeria. Though the coup failed, Babangida earned laurels of gallantry in the hearts of chroniclers of Nigeria’s military history. The coup was to be the graveyard of several fine officers of the army like civil war hero, General Iliya Bisalla who, till today, has a major road named after him in Enugu’s GRA, in appreciation of his efforts.

From his enrolment at the Nigerian Military Training College (NMTC) in Kaduna on December 10, 1962, monitors of his meteoric manifestations knew that young Ibrahim would have a consequential alliance with power. Enrolled with officers like Muhammed Magoro, Garba Duba and Ibrahim Sauda, Babangida’s imperishable footsteps are more in the annals of the history of his romance with power than they were with his military chosen career. Towering high among the core of officers who seized power from President Shehu Shagari in 1983, IBB was said to have suggested Buhari, among the coup plotter triumvirate, as one to rule the country. He was subsequently displeased that Buhari, just three months his senior in the army, would allow his deputy, Brigadier General Tunde Idiagbon, a junior officer to the coup triumvirate, ride roughshod over those of them who sacrificed their lives to get Buhari to be Head of State. IBB was said to have been slated for retirement over his impudence at having walked up to the C-in-C one day to remind the Head of State that the man he recently retired from service was a beneficiary of the triumvirate. IBB struck months after to save own neck and rescue the said beneficiary from the vice grips of the C-in-C. Upon IBB’s ascendancy as military president, his hijack of power evoked smiles on the faces of Nigerians, even though they were later to regret his rule.

Babangida had a very lethal hold on power that sent shivers down the spines of those who attempted to test his resolve. His walked the path of Niccolo Machiavelli. Machiavellianism, a political treatise of Niccolo, 16th-century Italian diplomat and political theorist, has gained scholarly examination as a cruel, blood-cuddling method of power usage where the triad weapons of persuasion, manipulation and deception, rather than raw, crude brunt, are deployed as the weaponry of power. Psychologists claim that Machiavellianism also possesses personality traits of narcissism and psychopathy.

Babangida heavily deployed these tropes in his usage of power. In his The Prince, Machiavelli propounded a cruel path for his faithful in power to tread. This is epitomized in one of his teachings, to wit, “If an injury is to be done to a man, it should be so severe that the prince is not in fear of revenge.” In abidance with this code, Babangida traded many irrecoverable tackles against his adversaries from which they never recovered until they sank into their graves.

At the height of office in the 1990s, he had told interviewers who marveled at his eclectic disposition to power that he was fascinated by the rulership traits of Zulu war hero, Chaka and Hannibal. The latter was a war General and statesman from Ancient Carthage widely held to be one of the greatest military commanders in history. A common thread that runs through both Generals is their maniacal and deadly power calculus, as well as their uncommon tactics and strategies in mowing down adversaries. Like Chaka and Hannibal, Babangida deployed hegemonic weapons of vinegar and juice in his dealings with friends and foes of his government. The juice resulted in the debasement of values that permeates Nigeria today.

But Babangida was not all brunt and bruises. With a disarming smile and an effeminate gap-tooth that masks the monster of power in his grips, it is doubtful if there was or is any Head of the Nigerian State in recent history who possesses IBB’s kind of suavity, brilliance and even imperishable imprints in office. He was Janus reincarnate. While those who interfaced with him saw a very compassionate, humane and passionate character, Nigerians saw a very deadly and brutal leader who could sacrifice a city to rescue an armoury akin to the teaching of Machiavelli. He had a midas-touch which ensured that those who came across him didn’t forget him in a hurry, either for good or bad.

Unlike what we have today, Babangida dialogued with the people consistently. He never took them for granted. As if acting out the script of The Prince, he ran a government that made the people vicariously take ownership of the most crucial but painful sacrifices they had to make. He pioneered a romance with theoreticians of socio-politics, a romance which produced brilliant policies of government like DIFFRI, MAMSER, Code of Conduct Bureau, People’s Bank, mortgage bank, primary healthcare centers across the country. He created many agencies which today straddle our economic life. They are the Federal Environmental Protection Agency (FEPA) which he created in 1985 and the Oil Minerals Producing Area Development Commission, construction of the Third Mainland bridge, construction of the Federal Capital Territory and universities of agriculture and technology across the country. He appointed world-class scholars and technocrats as his ministers like Olikoye Ransom-Kuti and created many states and local governments which, for good or bad, constitute the architecture of governance today. No leader in Nigeria’s history has Babangida’s reputation for deploying palliatives as a weapon for stemming the tides of dissent. For instance, he ran a government by referendum, even while implementing polices said to have been imposed by Bretton Woods. Before the austerity measure policy, for instance, IBB laid the policy by the table of Nigerians to discuss, making its ultimate implementation a fait accompli.

His Structural Adjustment Programme, (SAP) implemented in 1986, brought an unprecedented deregulationof the agricultural sector, abolition of marketing boards, massive privatization of public enterprises and devaluation of the Naira. It brought unprecedented pains to the people as well. IBB hired the best of Nigeria’s brains resident in the academy and used them to surf a template of governance for Nigeria. In most of those experiences, theory failed governance and academics gathered a renowned notoriety as hollow propounders whose political economy remedies for redemption of the polity were at best Utopian. In spite of the high-falutin policies, Nigerians were not better of economically and the ascendancy of bribery, corruption, cronyism and a rent-seeking economy which he instituted became the hub of Nigeria’s socio-political malady. The country still battles it till today.

During his eight-year reign, Babangida’s government left traces of blood which though are coagulated now, still stain his cocaine-white apparel. Prominent among this is the blood of journalist, Dele Giwa, parcel-bombed in a novelty murder unknown in the history of the macabre of government in Nigeria. The widely-circulated tale of Gloria Okon, said to be a drug courier and alleged to be acquainted with him, is yet unresolved. IBB was intolerant of dissent and had a dual response to it: cooption or evisceration.

It is a shame that, 26 years after he left government, no Nigerian leader has manifested IBB’s brilliance, grasp of governance and the democratic credentials he possessed, even as a military despot. For instance, while we today battle to be told what ails our president, Babangida advertised his sickness before Nigerians almost 30 years ago and subsequently travelled to Germany for surgery. Radiculopathy, he claimed, was the surname of the infirmity. He also said he still had pellets lodged in his leg since the civil war. Nigerians collectively prayed for his quick recovery. After him, so-called leaders in a democracy have disdained disclosure, shawling their existential lot of infirmity from their constituents, as if by being president, they had automatically become German philosopher, Fredrich Nietzsche’s Superman. While he took ill and was being ferreted to Saudi Arabia for treatment in 2009, I wrote a piece against President Umaru Yar’Adua which some people felt was callous. It was entitled Why we should neither fast nor pray for Yar’Adua. My argument was that, since he didn’t disclose that he was sick, it would be foolhardy for Nigerians to pray for his recovery.

Babangida, however, further ruined what was left of his credentials by his failure to abide by democratic norm when he reneged on his promise to hand over power in 1993 and annulled the June 12, 1993 election. By the way they show us that, comparatively, Babangida was a hero, the crop of leaders after him has shown that his creed of benevolent dictatorship is what is needed in a democratic experiment of this sort. Not effeminates or pacifists.

One unique thing about Babangida is that he still has his ‘boys’ in all the nooks and crannies of Nigeria today, retired Generals themselves, who are ready to die for him. I doubt if the current C-in-C has such. It is sincerely hoped that IBB, apart from all that have been written about him, will personally document all the missing links in his eight-year government and almost three decades, post-office. Like the Awujale ofIjebuland said last week at the Ojude Oba festival, death doesn’t haggle its day of strike. I digress: Since I read the biography of this great king – Awujale, I have come to reserve a space for him in my admiration. His standing up to Olusegun Obasanjo when he attempted to destroy Mike Adenuga caught my fascination.

Nigeria cannot afford to have the IBB recollections undocumented for posterity. By the way, there is a doctoral thesis that I have seen, presented in 1997 to the department of Political Science, University of Ibadan, which dissects what it called IBB’s neo-patrimonial rule, which we must encourage its author, Adeolu Akande, Professor of Political Science at Igbinedion University, Okada to get published. It theoretically documented IBB’s rule.

About a year ago, pictures of Babangida’s frail and apparently sickly frame appeared on the social media and some ostensibly naïve characters took their time to mock the Prince of the Niger. They should be told that sicknesses and death, Siamese twins of providence’s sting of man, are analogous to a fitful downpour that is yet to subside which no one can claim to be immune from its anger. IBB is battling his own existential portion. We are or will all battle ours too. I raise a wine glass up to celebrate Nigeria’s most controversial leader.

Dr Festus Adedayo sent this in from Ibadan