The transformative power of infrastructure in driving economic prosperity is a well-established principle, as eloquently articulated by the visionary American President, John F. Kennedy: “American roads are good not because America is rich, but America is rich because American roads are good.”

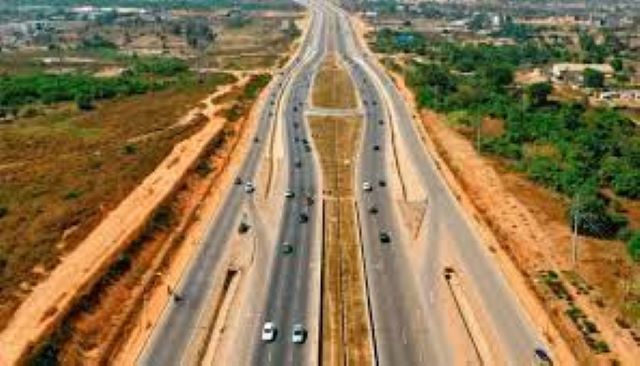

This sentiment resonates strongly with Nigeria’s ongoing Lagos-Calabar corridor project, which encompasses a high-speed railway and a 10-lane coastal highway, stretching 700 kilometres from Lagos State, the acclaimed fifth largest economy in Africa, into the heartland of the oil-rich Niger Delta.

Transforming Nigeria’s fortunes

The linkage between Lagos and Niger Delta will serve as a vital artery for economic activity, with key projects such as the Lekki Deep Sea Ports, Eko Atlantic City, Lekki Free Trade Zone, and the Dangote Refinery along its route. This economic corridor can, as some analysts have projected, double Nigeria’s GDP[1][2][3] when fully operational, transforming Nigeria’s fortunes[4]. The improved access to scenic coastal beauty, coupled with the historical and cultural treasures along the route, positions the corridor as a potential tourism haven, creating new jobs, boosting local economies, and showcasing Nigeria’s diverse cultural heritage to the world.

Democratising Infrastructure Landscape

Though Nigeria’s democratic Fourth Republic is in its 25th year, our infrastructure landscape still bears the vestiges of our colonial and militarised past, with the most significant infrastructures being those constructed by our former overlords.

For instance, there are four ‘A’ roads that connect Nigeria’s northern and southern parts – a reflection of our colonial past, which successive administrations have maintained. To move beyond a “colonial and militarised mentality,” the Lagos-Calabar Road will be the first ‘A’ road connecting one end of the southern region to the other, constructed by a civilian administration.

It embodies a commitment to building a modern, efficient infrastructure network that caters to the needs of a growing and dynamic economy. When completed, the road will probably become the favourite, fastest, and easiest access route in and out of the South-South region, Nigeria’s neglected golden geese, as it covers all the six states.

Time Saved is Money Earned

Consider the example of travelling from Eko Hotels and Suites, where the Lagos-Calabar Road starts, to the Lekki Deep Sea Ports. Averagely, as monitored on Google Map, this 81 km journey takes 1 hour and 50 minutes. The Lagos-Calabar Road, with its optimised…

DG, DAWN Commission, Dr. Seye Oyeleye walked the entire road at 1.5km on reconnaissance visit sign, will reduce this distance to 47.5km, potentially cutting travel times to an hour. Extrapolate this timesaving benefit over millions of trips annually across the entire corridor, and the economic impact becomes substantial. We are about to witness the same – maybe even better – economic miracle that the Third Mainland Bridge represents.

The road solves the twin problems of non-existent railway for cargo evacuation and the inadequacy of the existing road infrastructure to handle the expected traffic volume at the Lekki Deep Sea ports – which maritime experts have called attention to[5].

Beyond the Economy- Shoring Up Our Future

The Lagos coastline has suffered from decades of neglect, with the threat of ocean surges and shoreline erosion posing significant risks to communities and infrastructure. At one point, experts projected ocean surges would turn the whole of Victoria Island into a wasteland.

By taking cues from similar projects in other countries, the Lagos-Calabar Road can serve as a crucial shoreline protection measure, safeguarding the long-term sustainability of coastal communities. The ongoing shoreline reclamation efforts, with up to 8 metres of sand being dredged from the sea to reclaim the lost shoreline, are a testament to Nigeria’s commitment to addressing this pressing environmental challenge.

Addressing Transport Poverty Indicators

Transport poverty is a harsh reality for many Nigerians, particularly those in rural and underserved areas. The Lagos-Calabar coastal road and railway offer a lifeline to communities trapped in a cycle of poverty because of limited access to transportation. Businesses will benefit from improved logistics, reduced transportation costs, and faster delivery times, as they can efficiently transport agricultural produce and refined petroleum products. This increased efficiency could translate to more profits for businesses and lower prices for consumers, empowering individuals and fostering economic growth.

Addressing the Concerns

The contract bidding processes, absence of an ESIA study, and debates over national priorities have generated criticism for the Lagos-Calabar Road project.

Advocates of national priority, adopting the editorial of a news medium[6] as their manifesto, contend that there are issues warranting more attention than the Lagos-Calabar road project, particularly the extensive lineup of road rehabilitation projects undertaken by previous administrations.

According to the editorial, there is no solution to the urgency of now in a road project that will take eight years to complete, and that the loans secured by the Tinubu administration “should not be frittered away on a white elephant projects that will not positively impact the economy in the short and medium terms.”

It is important to note that the Lagos-Calabar Road project breaks away from the norm by having phases tied to economic projections, unlike the usual practice of deciding milestones based on the number of kilometres allocated to the northern and southern parts of the country.

While he was the minister of works between 2016 and 2023, Babatunde Raji Fashola, SAN, said there were 13,000 roads under construction and he delivered 9,290km of completed road sections across the country[7]. Despite these impressive road construction and rehabilitation milestones, the economic impact within the same period was minimal because of a lack of specific economic projections tied to the projects.

Also, noting that the lifespan of an asphalt road is between 10-15 years, we should expect that many of those rehabilitated sections would need maintenance by now. Therefore, because of this lack of a nexus between road construction and vital economic policies, our roads hardly deliver any economic benefit before needing significant rehabilitation. Indeed, all major roads remained incomplete within this period, except for the ones executed under special funding, like the Apapa-Oshodi expressway funded with tax credits.

The road construction approach in Nigeria, focusing on simultaneous projects without clear economic objectives, has resulted in roads becoming financial liabilities instead of economic assets, impeding their long-term impact and sustainability. How can we effectively monitor 13,000 roads? Dave Umahi, the current minister of works, publicly accused a construction firm of using substandard materials on national TV and accused the site engineer of connivance. Take, for instance, the Lagos-Ibadan expressway, the rehabilitation of which started in 2014. It is still under re-construction as we speak and some portions that were rehabilitated earlier already needed maintenance. This is the blind alley being touted as national priority.

In contrast, the construction of the Lagos-Calabar road’s first phase directly connects key economic projects, such as the Lekki Deep Sea Port and the Dangote Refinery, creating an industrial hub. Experts project that this connection will generate substantial revenue, with estimates suggesting it could add at least $1 billion annually to Lagos State’s revenue[8]. This shows the considerable economic advantages that the road project can offer in the short and medium term. For context, the generated revenue of Lagos State in 2023 was N651bn, accounting for only 37% of the state’s budget.

Critics have also highlighted the need to prioritise funding for social sectors such as health and education over infrastructure projects like the Lagos-Calabar Road. While these sectors undoubtedly require attention, it is essential to consider whether existing resources can adequately address their challenges or if alternative strategies, such as infrastructure developments, can generate additional resources to tackle these issues effectively.

Considering the allocation of funds in Nigeria’s security sector over the past decade is also an important perspective to this debate. Despite significant investments, security challenges persist with significant improvements only in the North-east region and marginal improvements nationwide. Some governors, including Katsina State governor Dikko Radda, have described our security management as “business venture[9]”.

Yet, we have not called for a halt to security allocations, where alleged mismanagement may lead to severe consequences. Therefore, the critics’ intentions are questionable, as they prefer stirring up controversy by demanding a stop to the Lagos-Calabar Road project because of legal matters that can be addressed in court.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s population is expanding rapidly and we would need new, durable and viable infrastructure to accommodate this growth. Through the Lagos-Calabar corridor, Nigeria can ensure not only economic prosperity but also environmental sustainability and social progress. Global examples, like Spain’s N-340 coastal highway and Vietnam’s Reunification Express railway line, prove that such infrastructure is a major enabler of investment from both local and foreign investors. Nigeria can utilise the Lagos-Calabar corridor to unlock its own tourism and trade potential, attracting investments in hospitality, leisure, and cultural preservation.

As President Kennedy’s words remind us, prosperity is not a result of wealth; it results from wise investments in infrastructure. The Lagos-Calabar coastal road and railway represent a transformative investment in Nigeria’s future, unlocking economic opportunities, protecting our environment, and addressing social inequalities. When put on a weight, the pros of this project far outweigh the totality of the cons being advanced in some quarters.

Rather than the cacophonous opposing views, we should advocate for proper designs, milestones linked to economic projections, and strategies that can safeguard coastal communities.

Written and edited by Segun Balogun, Senior Analyst, additional research by Abiodun Abioye, Associate

[1]https://theconversation.com/nigerias-new-lekki-port-has-doubled-cargo-capacity-but-must-not-repeat-previous-failures-197426

[2] https://nairametrics.com/2023/01/24/lekki-port-to-contribute-361bn-economic-impact-in-45-years-icrc/

[3] https://businessday.ng/uncategorized/article/eko-atlantic-city-to-contribute-over-1bn-to-nigerian-economy/

[4] https://www.worldfinance.com/infrastructure-investment/lekki-free-zone-set-to-transform-nigerias-fortunes

[5] https://guardian.ng/business-services/why-lekki-deep-seaport-should-avoid-pitfalls-of-lagos-ports-by-stakeholders/

[6] https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/691629-editorial-a-coastal-highway-of-misplaced-priority-and-due-process-abuse.html

[7] https://guardian.ng/news/fg-delivers-8938-housing-units-9290-km-roads-fashola/

[8] https://businessday.ng/uncategorized/article/eko-atlantic-city-to-contribute-over-1bn-to-nigerian-economy/

[9] https://punchng.com/banditry-now-a-business-venture-for-govt-officials-security-agents-others-katsina-gov/

- This article was packaged by the Development Agenda for Western Nigeria (DAWN COMMISSION)